We’ve covered the components of an Arterial Blood Gas test, discussed pH, the partial pressure of gases, and worked through a basic ABG case study. I promise, this will all make sense at the end. I know there are mnemonics and tables and tricks to tell you what type of acid-base disorder your patient has. These are fine. But truly understanding the science behind these disorders will make your clinical practice better. Stick with it; you’re doing great!

Back to Basics

Today, I want to share a nifty little calculation to monitor a patient’s respiratory status: the p/F ratio.

We have been throwing around a bunch of letters and numbers in regards to ABG and respiratory status. A quick review:

PaO2: this is a measure of how much oxygen is held in the blood. Oxygen is a gas and exerts a pressure on a closed container (such as a lab tube). Measuring this pressure — the ‘partial pressure’ — tells us how much oxygen we’re working with.

FiO2: is the fraction of inspired oxygen. Room air at sea level is 21% FIO2. Every liter per minute we add increases the FiO2 by 4%.

Knowing these 2 numbers, we can calculate the p/F ratio.

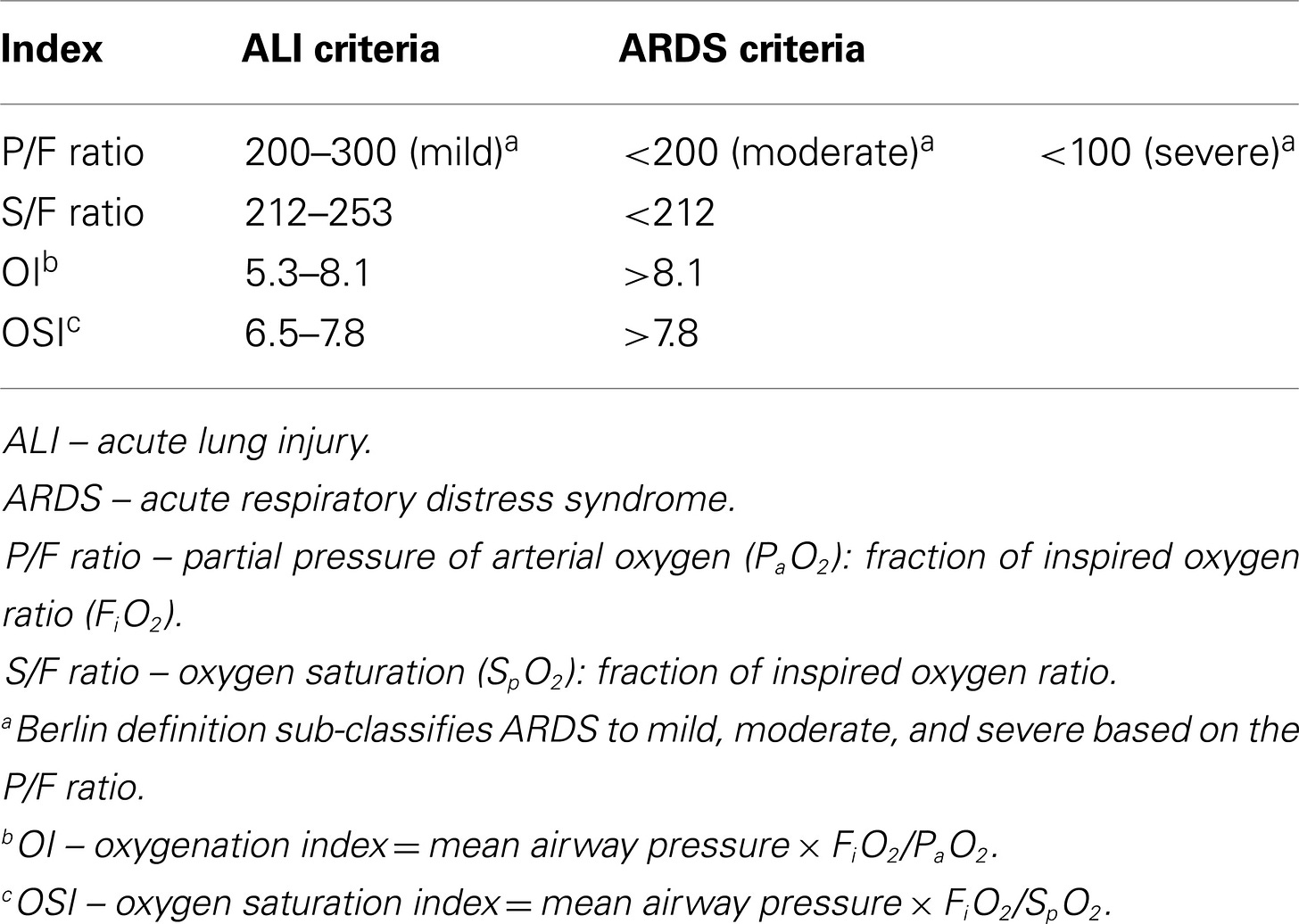

Why, you ask? This gives us a quick measure of lung function, specifically when looking at Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and respiratory failure.

ARDS is a real crappy thing that happens after lung injury due to infection or inhalation injury. Basically, the lung tissue is damaged and instead of repairing itself back to lung tissue, it liquifies and turns into scar tissue. As you can imagine, scar tissue doesn’t work very well to transport oxygen. Mortality can be over 50%.

So, what’s a normal p/F ratio? Let’s pretend you’ve pulled an ABG on me and done the calculation. I’m breathing room air (21% FiO2) and my fictional PaO2 is 95.

(95/21) x 100 = 452.

Yay! My respiratory system is working just as it should.

Bedside Considerations

Let’s continue with the same case study as the previous ABG Nurse Files. We have an elderly person with acute hypoxia, with a crummy looking chest x-ray and increased O2 demands.

We’ve gotten an ABG and the results are: pH = 7.33, PaO2 = 60, PaCO2 = 37. The patient is on an oxymask at 6 lpm. Let’s plug this into the p/F ratio equation (p/F x 100) and see what’s up.

PaO2 is 60 mm/hg and FiO2 = 45%.

(60/45) x 100 = 133

Ick. That’s not good. This patient is in critical respiratory failure and needs immediate intervention.

Now, there are lots of guidelines for what numbers mean which stage of distress. When in doubt, treat the patient. I don’t care if they don’t quite meet the guidelines for severe versus critical failure. If they are in distress, we need to get them out of distress and quickly.

ADS does have a specific guideline, as it is a different type of lung injury. You can be in respiratory failure without ARDS. Remember ARDS is the actual destruction of lung tissue, rather than a failure of function of lung tissue.

But wait, what if I can’t get an ABG drawn due to impaired circulation, low blood pressure, or an unreceptive attending provider? How can I prove that something needs to be done?

You can calculate an s/F ratio, where ‘s’ is the SpO2 and ‘F’ is the FiO2. The s/F ratio has been proven to correlate to a p/F ratio when you are unable to obtain a PaO2 or need to do something noninvasive.

The process is the same:

SpO2 is 90% and FiO2 is 45%

(90/45) x 100 = 200

The numbers aren’t quite the same, but correlation has been proven in varying populations by multiple studies.

By whatever measure we use, we can show with cold, hard numbers that this patient is in distress and needs intervention. Whether that is Invasive Non-Invasive Mechanical Ventilation is a discussion that needs to happen ASAP. Get your provider down to see the patient as soon as possible before they progress to full respiratory failure and circulatory collapse.

Keep at it! This is complicated topic. You’ve done a good job so far. A few more installments and you’ll be interpreting your ABGs — and treating your patients — like a champ.

References

Porth’s Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States (9th Edition). Grossman, S.C., Porth, C.M.

Thank you for reading! You can follow me on Instagram and subscribe to this newsletter to stay up to date with posts, practice NCLEX questions, and my stories of life as an inpatient nurse.

If you found this article interesting, useful, or entertaining, please consider donating via a subscription. All This Is My Nurse Face content is free, but you can choose a subscription to help support my writing. My goal is to educate and inspire healthcare professionals and laymen alike. Your support helps me achieve that!

Also, please check out my other Substack: WritingRampant. No nursing, but occasional blood and guts. (My characters like to stab each other. Such drama queens...)

Enjoy!

Anna, RN, BSN, CCRN

Necessary disclaimer: I am discussing medications and medical conditions in this article based on my personal experiences as a nurse. Your facility may have different requirements and resources. Use your own nursing judgement to assess and treat your patients according to your governing body and facility guidelines. All information within this article is correct to the best of my knowledge, but should be confirmed through verified evidence-based sources. I am not responsible for any clinical decisions made based on this article.